Our mygalomorph residents:Uh, what did you just say, Sheryl? Mygalomorph? What the heck is THAT? Well, you’re in luck today because I’m going to tell you. The funny-sounding name refers to one of two groups of spiders. Mygalomorphae are large-bodied, long-living spiders, such as tarantulas, purseweb and trapdoor species. The other spider group is called Araneomorphae, which includes nearly all the other “true” spider groups – jumping spiders, wolf spiders, orbweavers and lynx spiders, to name only a few.

Lucky you again – now I’m going to share the four mygalomorph spider species that I’ve documented in our yard. I’ve recently spent several hours, researching them so I can better understand their differences myself.

Mygalomorphae Unveiled: Venom, Habitats, Diets, and Life Cycles Explored

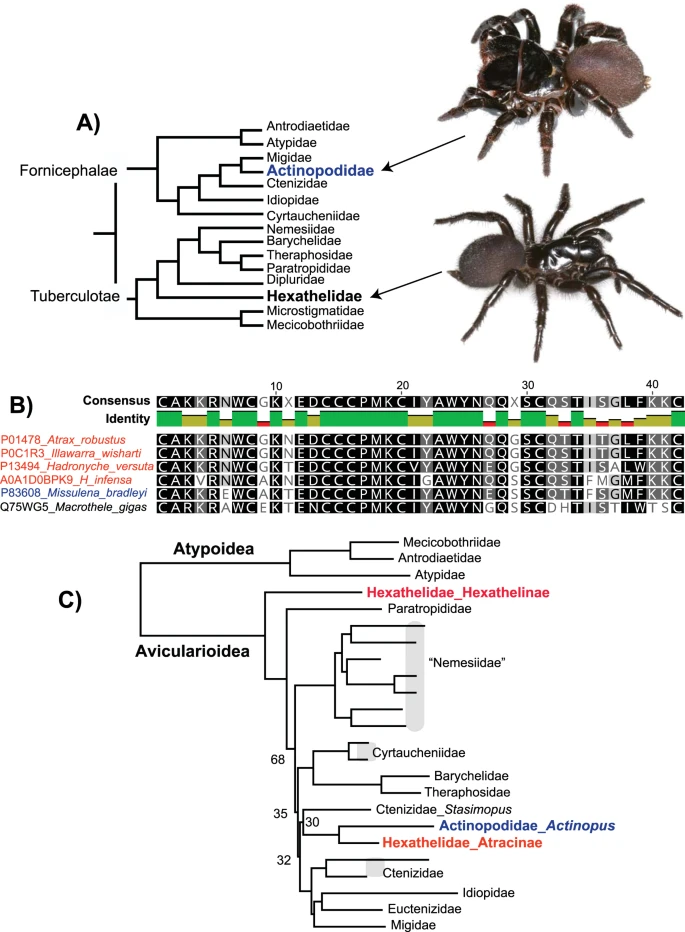

The suborder Mygalomorphae encompasses some of the most formidable and captivating spiders, including baboon spiders and trapdoor spiders. These arachnids are considered among the more primitive groups of spiders, with fossil evidence tracing their lineage back to the Triassic Period. Notably long-lived, some individuals can survive for up to two decades in captivity. Presently, 15 families of mygalomorph spiders are recognized globally, with 11 found in the Afrotropical Region and 10 in Southern Africa, represented by numerous genera and species.

Most mygalomorph species are terrestrial, dwelling in silk-lined retreats that vary in structure. These retreats take the form of burrows of differing shapes excavated in the soil or sac-like chambers nestled beneath rocks or affixed to tree trunks. The entrances may either remain open or be sealed with a silk-and-soil trapdoor. Primarily nocturnal, these spiders remain concealed in their retreats by day, emerging at night to ambush passing prey or actively hunt. Their diet consists of a variety of insects and small animals, rendering them integral components of the ecological food web.

Mygalomorphs are renowned for their remarkable longevity, often exceeding 25 years. Certain desert-dwelling wolf spiders, such as those belonging to the families Zodariidae and Sparassidae, exhibit life cycles extending beyond two years. Adapted to harsh environments, these spiders can endure prolonged periods of fasting by sealing themselves within their retreats (Main, 1976). In contrast, non-burrowing spiders typically complete their life cycles within a single year. While their existence is more precarious than that of burrowers, they possess the advantage of recolonizing disturbed habitats through the aerial dispersal of juvenile spiders, particularly in areas affected by drought or wildfires.

Breeding and Dispersal

The reproductive cycle of the Australian trapdoor spider Anidiops villosus is synchronized with the autumn and winter rains. Maturity is reached in early autumn, at which point males abandon their burrows in search of females. After mating, the males perish. Concurrently, the brood from the previous year’s mating season emerges from the maternal burrow, dispersing to establish their own shelters (Main, 1978).

Similarly, research by Shook (1978) on Lycosa carolinensis in the Lower Sonoran Desert revealed seasonal patterns of activity. Both adult and immature spiders remain inactive from November through February. Immature spiders peak in numbers during March and October, while females and males reach their highest populations in June and July, respectively. Female Lycosa carolinensis carry eggs in late July and late August, potentially producing two broods per year. However, they likely do not reproduce until their third summer, after which they may live for another year. Males also mature by their third summer but die shortly after mating.

Many arthropods exhibit seasonal acclimatization to temperature fluctuations, and geographically separated populations may develop genetic variations in their thermal tolerance (Cloudsley-Thompson, 1970). Such seasonal metabolic adjustments have been documented in Lycosa carolinensis by Moeur & Eriksen (1972).

Distribution and Research Advances

The infraorder Mygalomorphae comprises nearly 3,000 species with a global distribution, approximately one-third of which inhabit the Neotropical region. Compared to their araneomorph counterparts, knowledge regarding mygalomorph biology remains relatively limited. However, recent research—particularly in the Neotropics—is progressively bridging this knowledge gap. Studies have yielded valuable insights into mygalomorph foraging strategies, communication, reproductive biology, habitat selection, and defense mechanisms against predators.

General Behavior of Mygalomorphae

Mygalomorphs are a remarkably diverse group, with the majority (except the Microstigmatidae) residing in silk-lined retreats. These retreats take the form of vertical burrows or chambers beneath rocks or tree bark, often equipped with silk trapdoors. Certain species construct additional structures, such as lids, signal threads, collars, turrets, or catch webs, to enhance their ability to detect prey through substrate vibrations sensed via their palps and legs. Prey is typically captured at or near the retreat entrance. The evolution of trapdoors and other structural adaptations has occurred independently multiple times.

Unlike most mygalomorphs, members of the Microstigmatidae family are free-roaming and do not construct burrows or webs, instead seeking shelter beneath forest debris. Mygalomorphs are predominantly nocturnal, with some species venturing out at night in search of food, while others remain at the entrance of their retreats, poised to ambush prey.

The Advantages of Burrow Dwelling

Burrows offer numerous survival benefits to mygalomorphs:

- Protection from predators and parasites

- A secure environment for eggs and developing spiderlings

- A sheltered space for molting

- A safe location for mating

- An effective hunting strategy for ambushing prey

- A refuge during periods of inactivity, particularly in winter

- Flood resistance, as their silk-lined burrows repel water

- Safety from wildfires, as spiders retreat deeper into their burrows

- Thermal stability, as burrow temperatures and humidity levels remain relatively constant

- Defense against fungal and bacterial infections due to the antimicrobial properties of their silk

Mygalomorph Families and Their Retreats

| Family | Type of Retreat/Burrow |

|---|---|

| Atypidae | Silk-lined burrow with an excavated chamber covered in silk, used as a prey trap |

| Barychelidae | Variable silk-lined burrows with multiple entrances, some featuring leaf or grass turrets, or shallow retreats under stones with trapdoors |

| Ctenizidae | Silk-lined burrows with rigid, cork-like trapdoors, either circular or D-shaped |

| Cyrtaucheniidae | Single silk-lined burrows, sometimes with side passages; frequently Y-shaped with flexible wafer trapdoors or sealed with mud pellets |

| Dipluridae | Tubular or funnel-shaped silk retreats in crevices, extending into interconnected funnel- or sheet-like webs |

| Idiopidae | Silk-lined burrows or chambers, often sealed with wafer- or cork-like trapdoors |

| Microstigmatidae | Free-roaming, sheltering beneath debris on the forest floor |

| Migidae | Arboreal sac-like retreats or terrestrial silk-lined burrows with flap-like trapdoors |

| Nemesiidae | Silk-lined burrows, either single or Y-shaped, or silk-lined tunnels and chambers beneath rocks |

| Theraphosidae | Silk-lined burrows or silk-lined chambers under rocks, typically lacking a trapdoor but often covered with a thin silk layer when unoccupied |

The Mygalomorphae suborder represents a lineage of spiders that have remained evolutionarily distinct for millions of years. Their intricate behaviors, remarkable longevity, and highly specialized burrowing techniques continue to intrigue researchers and enthusiasts alike. Ongoing studies will undoubtedly yield further discoveries about their ecological roles, evolutionary history, and conservation significance.